Tokyo, Japan- Emotional disorders, such as anxiety and depression are about 3-fold more common in adult women than in adult men. Biological and neurogenetic considerations aside, these gender differences have commonly been ascribed to structural gender inequity (e.g. family care burden, employment prospects, disparities in remuneration), or to culture-dependent factors. On the other hand, depressive symptoms very often first become manifest during adolescence, when the impact of structural inequalities would be expected to be minimal. While girls have higher rates of depression as compared to boys, it remains unclear as to whether the trajectories of depression in adulthood develop in a linear fashion in the two genders, and if so, whether they can be sufficiently explained by structural factors alone.

Recent work involving researchers from Japan (including Kiyoto Kasai from the University of Tokyo’s International Research Center for Neurointelligence) and the UK (led by Gemma Knowles of Kings College London) adds a new dimension to our understanding of the underpinnings of gender-dependent differences in depression. Their work, published in Lancet Child & Adolescent Health, suggests the potential importance of local social experience in girls’ greater vulnerability to depression.

In contrast to previous cross-sectional research in this area, a longitudinal cross-cohort approach was here used to assess depression in 7100 young persons in two large cities in Japan and the UK. Crucially, while these two countries are similar in terms of economic development, they differ markedly in terms of gender equity according to 2023 The Global Gender Gap Index (GGGI) computed from indicators of economic opportunity, education, health and political leadership: in 2023, the UK and Japan ranked 15th and 125th, respectively, out of 146 surveyed countries, on the GGGI. Each of the cohorts, the Tokyo Teen Cohort (TTI) and the Resilience, Ethnicity and Adolescent Mental Health (REACH) cohort, comprised an approximately equal number of girls and boys that shared sociodemographic characteristics. Depressive symptoms experienced in the preceding 3 weeks were assessed by the Short Mood and Feelings Questionnaire (SMFQ). Longitudinal confirmatory factor analysis demonstrated to be insensitive to the effects of country, gender and age. Trajectories of depression (SMFQ scores) for girls and boys between the ages of 11 and 16(when typically inequalities in emotional health between girls and boys become manifest) were estimated using linear growth curve models.

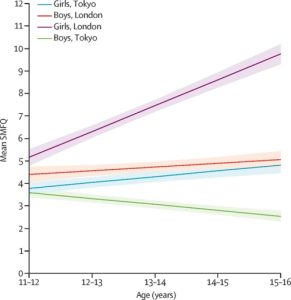

Key findings from this study are summarized in Fig. 1. Gender-related differences in the emergence of depressive symptoms were observed slightly earlier in the London (REACH) cohort than in the Tokyo (TTI) cohort (11-12 vs. 11-14 years), with girls in both Tokyo and London showing stronger symptoms than boys in their respective cities. Analysis revealed that mean SMFQ trajectories are influenced by age, gender and location: depressive symptoms increased between the ages of 11 and 16 in both genders in the London cohort and, albeit to a lesser extent, in Tokyo girls; in contrast, there was a downward trend in depressive symptoms among Tokyo boys aged 11-16 years. Overall, the annual rate of increase in depressive symptoms was around 4 times greater in 16-year-old London girls as compared to their Tokyo counterparts and strikingly, the levels of depressive symptoms among boys and girls in London were about twice higher than those in their peers from Tokyo.

Given the widely different measures of gender equity in the UK and Japan, the results of this study question the magnitude of the impact of gender equity on emotional health. In fact, since both the UK and Japan have comparable economies, the findings rather point to a role for one (or more) socio-economic factors that contribute to the differential vulnerability of girls living in London vs. Tokyo to developing depressive symptoms. For example, greater income inequality, coupled with austerity measures, in the UK as compared to Japan is a potential cause of the observed differences since they increase child poverty, adversely impact population health, and force girls to take on adult roles and responsibilities at an earlier age. Such economic realities may translate into social problems such as violence and interpersonal crime – more common in London than in Tokyo – which correlate strongly with poor emotional health. Notably, the GGGI of gender equity does not consider sexual harassment, assault and intimate partner violence, and attitudes towards such violations; in this regard, Japan appears to perform better than the UK. Another potential contributor to the high rates of depressive symptoms in London girls may reflect an interaction between gendered discrimination and racism: multiethnicity is more prevalent in the UK than in Japan.

A unique feature of this work is that it was co-produced with cohort members, some of whom had depressive symptoms, as well as with ten young researchers aged 18-20 from Japan and the UK. The cohort members completed the SMFQ while the young researchers discussed possible interpretations, explanations, and implications of the results, and helped in writing the article.

Insights gained from this study provide a strong basis for filling the gender gap in mental gap by improving understanding of the social contexts and conditions that trigger poor mental health in girls which may ultimately predispose them to emotional disorders in adulthood. The results of this work also have implications for health policy by highlighting the distinction between gender equality and gender equity when examining gender differences in the incidence and prevalence of psychiatric conditions: while equality does not necessarily include deeply ingrained biases, equity or fairness addresses the need for creating inclusive environments.

The study was funded by the Invitation Program for Foreign Researchers at the Tokyo Metropolitan Institute of Medical Science, the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC), the ESRC Centre for Society and Mental Health, the Japanese Society for the Promotion of Science, and the European Research Council.

###

Referenced article: Knowles G et al (2025) Trajectories of depressive symptoms among young people in London, UK, and Tokyo, Japan: a longitudinal cross-cohort study. Lancet Child & Adolescent Health. doi.org/10.1016/s2352-4642(25)00059-8.

About the World Premier International Research Center Initiative (WPI)

The WPI program was launched in 2007 by Japan's Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT) to foster globally visible research centers boasting the highest standards and outstanding research environments. Operating at institutions throughout Japan, the 18 centers that have been adopted are given a high degree of autonomy, allowing them to engage in innovative modes of management and research. The program is administered by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS).

See the latest research news from the centers at the WPI News Portal: https://www.eurekalert.org/newsportal/WPI

Main WPI program site: www.jsps.go.jp/english/e-toplevel

About International Research Center for Neurointelligence (WPI-IRCN), The University of Tokyo

The IRCN was established at the University of Tokyo in 2017, as a research center under the WPI program to tackle the ultimate question, “How does human intelligence arise?” The IRCN aims to (1) elucidate fundamental principles of neural circuit maturation, (2) understand the emergence of psychiatric disorders underlying impaired human intelligence, and (3) drive the development of next-generation artificial intelligence based on these principles and function of multimodal neuronal connections in the brain.

Find out more at: https://ircn.jp/en/